At The Ringer’s request, Snarr analyzed every season from 2001-02 to the present to assess how many true “superstars” there are in a given year. To do so, Snarr rated players based on EPM, widely considered the gold standard of publicly available, all-in-one impact metrics.

The verdict? The NBA has seen a modest uptick in star quantity across the past 24 years—from an average of about 8.5 superstars in the first five seasons to 10 superstars in the most recent five-year span. There are seven players who would qualify this season, the same number as in 2001-02.

“It is more or less fairly flat,” Snarr says. “I really don’t know if that would be enough to support an expansion.”

What exactly makes an NBA superstar? A franchise player? How do we separate the superstar from the average star? Is it just the gaudiness of their box score stats? Or is it the players who, in modern parlance, impact winning the most? How much of stardom is about production (stats) vs. entertainment value (the guys you’d pay to see)?

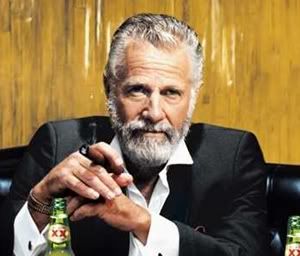

Because when you’re creating a team from scratch, you’re not just building a roster or trying to win games. You’re trying to build a following, to win hearts and minds. If your franchise star is Anthony Edwards, congratulations! People will pay to see him, win or lose. If your franchise star is Rudy Gobert? Well, he’ll make your team a winner, but you’ll need Edwards to score points and sell season tickets.

So, an obvious disclaimer: There’s a lot of “eye of the beholder” in these discussions, generally, even among the coaches, scouts, and executives who get paid to determine such things.

That’s why we turned to Snarr, a former analytics staffer for the Utah Jazz, whose EPM model and accompanying website, DunksandThrees.com, are universally respected in the analytics community. We needed an objective measure of a player’s impact. (Still: This remains an inexact science. Deciding where to draw the statistical cutoffs between various classes of “stars” is based in part on feel and, well, the dreaded eye test. Your results may vary.)

Using EPM, Snarr separated top players into three tiers: superstars (EPM of 2.4 and over in a given season), stars (EPM between 1.45 and 2.39), and significant contributors (EPM between 0.45 and 1.44). Those thresholds generally align with what you’d intuitively expect. The superstar tier last season included MVP Nikola Jokic (4.18), as well as Joel Embiid (3.70), Shai Gilgeous-Alexander (3.07), Luka Doncic (2.92), and Giannis Antetokounmpo (2.83). The second tier included everyone from, at the high end, Donovan Mitchell, Damian Lillard, and Devin Booker to, at the low end, Franz Wagner, Desmond Bane, and Trae Young. The third tier included Karl-Anthony Towns and Jaylen Brown down to Bradley Beal, Zach LaVine, and Malik Monk.

In short, you can build a contender around any of the Tier 1 guys. You can win a lot of games with the Tier 2 players, but you’ll probably need multiple of them to make a deep playoff run if you lack a Tier 1. And though some Tier 3 guys can play at a Tier 2 level in a given season, most of them are best suited as second or third bananas next to higher-tier stars.

To use an (admittedly tired) comic book analogy: The NBA is absolutely flush with Robins but still limited in its Batman supply. Pascal Siakam, Domantas Sabonis, and Bam Adebayo are fantastic talents and great supporting stars but ill-suited as leading men. Think of Mikal Bridges—a borderline All-Star and core-four player for a Phoenix Suns team that made the 2021 Finals but a miscast no. 1 in Brooklyn before a trade to the Knicks, where he’s again a fantastic fourth wheel.

If you look at Tiers 1 and 2 over the past decade, you find only a nominal increase in qualifying players—from a combined 30 players on average from 2001-06 to 34 from 2020-25. But dive into Tier 3, and a different picture emerges: It’s growing, substantially. Over the past five seasons, an average of 82 players per year qualified as Tier 3—up from 68 per year in the first five years of the analysis. There are 88 players in Tier 3 so far this season, compared to 66 in 2001-02.

So yes, it’s true: The league really is deeper than it’s ever been, with more talent and skill than we’ve ever seen. The data backs up the eye test. It’s just that the explosion of talent is mostly at the “significant contributor” level—the ace shooters, the lockdown defenders, the rim protectors, the indispensable starters who might make the occasional All-Star team but can’t carry a franchise.

Think of these tiers through the prism of the reigning champion Boston Celtics. They’re perennial contenders because of their superstar, Jayson Tatum (consistently Tier 1), and costar, Jaylen Brown (who varies between Tiers 2 and 3 in EPM), but they won the 2024 title on the strength of their top-shelf role players, like Derrick White, Jrue Holiday, and Kristaps Porzingis. Holiday has been an All-Star twice, Porzingis once, and White never. All three were in Tier 2 last season based on EPM. None of the three could carry a franchise on their own. (Even that trio combined on a roster lacking Tatum and Brown might struggle to win 41 games.)

Or consider the Zach LaVine and Brandon Ingram types—highly skilled, high-scoring players who have made an occasional All-Star team and earned max salaries but are best suited as complementary stars, not leading men. LaVine led the Chicago Bulls to a winning record just once in six seasons. Ingram led the New Orleans Pelicans to just two winning seasons in five years.

“How many of those players, the third-tier or middle-tier players, can you play through?” Snarr said.

All of which tracks with the general perception around the league.

“Most sports don’t have this huge disparity between the top players and the next tier down,” said another veteran Eastern Conference executive. “We have by far the largest gap of any sports between your top set of five to 15 to 20 players and the average player.”

Most teams today are in a perpetual scramble to find reliable, well-rounded rotation players—the sixth-through-10th guys who can be the difference between the playoffs and the lottery—and they’re not that easy to replace.

Or think of this all another way: In any given season, there are at least four to six teams that have no identifiable star—or even a second-tier star—to build around. It’s easy to dismiss the tanking teams, like Brooklyn and Washington, because they are bad by design. But consider the Utah Jazz, who have a legitimate star in Lauri Markkanen and are terrible anyway. Or the Portland Trail Blazers, who have accumulated some blue-chip talents (Scoot Henderson, Shaedon Sharpe, Donovan Clingan) but still can’t win half of their games. Or the Chicago Bulls, who got nowhere for years despite acquiring high-priced talents like Zach LaVine, DeMar DeRozan, and Nikola Vucevic.

The reality is, star acquisition in the NBA is a zero-sum game. There are a finite number of true superstars and a slightly larger (but also finite) group of Tier 2 stars in any given year—and those stars tend to gravitate toward one another. Every team with a solo star is trying to land a costar, or two. Which means that some teams have multiple stars, and some teams have zero. Add two more teams, and you’ll have two more franchises without a star—or hope. And even the best teams will likely lose some depth.

https://www.theringer.com/2025/02/18/nba/nba-expansion-teams-las-vegas-seattle-adam-silver-future

I don't think this take is controversial on a deeply divided Raptors board: the Raptors have multiple possibly 2nd and 3rd tier players, but no Batman/lead banana/superstar.