At first, the chariot was not harnessed to its greatest possibility. The earliest example, likely from Sumer, was more of a solid-wheel cart drawn by donkeys, used perhaps in war but more likely exclusively as an agricultural tool. But the Hittites and especially the Hyksos saw the possibility for more, and the Hyksos used the chariot to invade and conquer Egypt. At the time, Egypt — then in the decline of its Middle Kingdom — was weak and fragmented, and it was easily conquered. But the chariot still wasn’t being used properly.

Egyptians made the chariot much lighter. Faster. They trained horses specifically to pull chariots at high speeds. They used the lightest wood they could, often acacia, and used spokes to make the wheels as light as possible. There were shocks, making the platform stable enough that an archer could shoot accurately while on the move. With those improvements, Egypt reconquered the Lower Kingdom and even projected its power far into the Middle East. It was the height of Egyptian territorial expansion, coming hot on the heels of its lowest point. And it was all unlocked by optimizing a technology that to that point had never seen its ideal in reality.

Scottie Barnes must be one of the most unique stars in basketball. But, like the chariot, he hasn’t yet been harnessed in a way that fully unlocks his powers.

Most stars qualify as such because they’re just so good at putting the ball in the net. For most wings and forwards like Barnes, such scoring opportunities come via pick and rolls and isolations.

And Barnes does succeed in those playtypes. He spent long stretches last season as a pick-and-roll leader, with sky-high points per chance on such sets — particularly when seeing double picks. He came into the league a polished post and isolation player, and Toronto’s efficiency when Barnes sees the ball in those sets has long been terrific. Yet Barnes has done an uncommon share of his damage in such sets as a passer. In fact, if you isolate such plays to only include direct end-of-possession results (shots and turnovers), Barnes scored below 0.9 points per possession as a pick-and-roll handler and an isolation scorer last season. Both marks were below the league average.

It’s actually incredible, from that point of view, that he was still so efficient in such sets despite scoring at a below-average rate. And there were plenty of reasons why his scoring wasn’t more efficient: a high frequency of double-teams, the ability of defenders to stunt and gap quite liberally without fear of punishment, and opposing game plans that could focus entirely on him without worry. Yet, his scoring improved! In many ways, his improving efficiency on virtually every playtype was a reflection of his improved ability to reach the paint, to threaten defenses as a scorer, to force rotations: more passes only become available to players because of the threats they pose as a scorer. If you can’t score, you don’t have those passes available to you. And Barnes can score — 20 points per game on quite solid efficiency is nothing to scoff at.

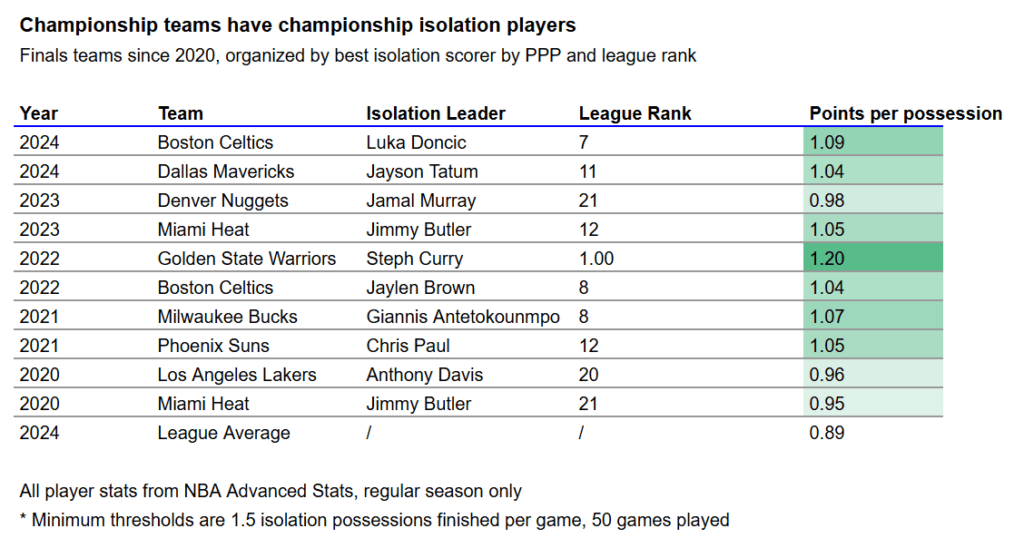

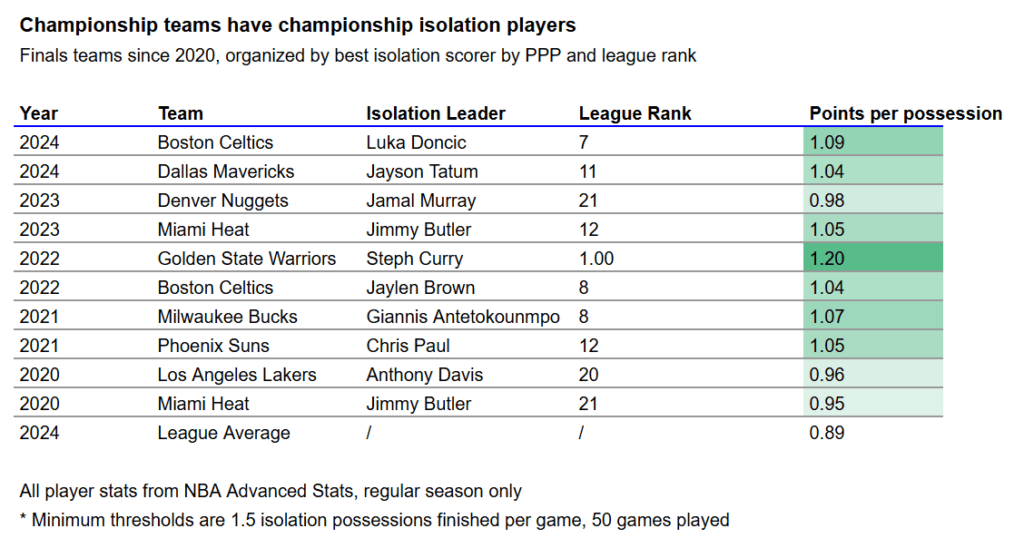

The thing is, the best teams have significantly more polished scorers. And in the hardest playtypes, too. In the NBA, there is a difference between a bucket coming off a cut, or a spot-up shot, or in transition — and one that you manufacture from a dead standstill, with all eyes on you. The best players of course need to be able to do all of the above. But the latter category is increasingly overlooked as a necessity on good teams. If you look at the last 10 teams to go to the Finals, every one rostered an isolation leader.